We recently spent five days in Sarajevo and had an incredibly eye-opening experience. Before this trip, I think the only thing I knew about the Balkans was that it was a dangerous place when I was growing up. I remember hearing about a lot of conflict there during my childhood, but none of the specifics ever really stuck. We’ve been given a unique opportunity here touring these war-torn countries and have tried to understand the history better through conversations with locals, visiting museums, and filling in some gaps through web research.

So what exactly happened in the 90s in the Balkans? Who were the instigators and what were the motives? We’ve been asking these questions a lot, often just to ourselves as we were confusedly trying to work through what we were learning. When we asked our landlord in Sarajevo for his perspective on what happened in the 1990s, he started by talking about the Ottoman invasions hundreds of years ago. Whoa! This is way more complicated than I ever realized if we have to go back five centuries to get the full picture. I won’t butcher that many years of history by trying to explain it in detail, but the gist I’ve taken away is that the Ottomans conquered much of the present day Balkans in the 14th and 15th centuries and were partially driven back out by Austria-Hungary starting in the 17th century. The next few centuries were dotted with strife, occupations, and changing borders, leading up to the Balkan Wars of the early 1900s where several Balkan nations joined together to defeat the Ottomans in Europe and then fought with each other over the recaptured territory. When Yugoslavia was formed in the early 1900s, it was called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, snubbing the roughly 10% of the population who were European Muslims, having been converted during the centuries of Ottoman occupation.

In the early days of Yugoslavia, it seems the Serbs and Croats were especially unhappy about Bosnia being its own country and had talks of splitting the country up between themselves. Those plans were first delayed by WWII and then furthermore by the reestablishment of Yugoslavia led by Josip Broz Tito at the end of the war. Under the dictatorship of Tito, Yugoslavia had several decades of relative unity and political peace. His death in 1980 paved the way for increases in ethnic tensions around the Balkans, and after communism fell across Eastern Europe in the ’80s, Balkan nations began declaring their independence, beginning with Slovenia and Croatia on 25 June 1991. Macedonia also declared independence later that same year on 8 September.

Meanwhile, Croatia and Serbia had secretly renewed talks about partitioning Bosnian land between them. Both countries already had numerous settlements within Bosnian borders largely occupied by Bosnian Croats and Bosnian Serbs. So when Bosnia declared its own independence in March of 1992, which was internationally recognized on 6 April 1992, Serbia in particular came unglued. The Serbs immediately began shelling Sarajevo (on 6 April 1992) and declared independence for the Republika Srpska, which was a large portion of territory within Bosnian borders. What followed was almost four years of largely defenseless Bosnians being terrorized by Serb forces. Sarajevo was shelled daily for over 3.5 years, averaging about 300 shells per day. Over 11,000 people were killed in Sarajevo, mostly civilians including around 2,000 young children. Our landlord pointed to the hills across the valley from our apartment and said that’s where the snipers used to take aim. He explained how the whole city had no electricity or running water for four years. He himself was shot in the arm as a civilian just trying to survive the siege. There were other atrocities committed that I won’t go into detail about, but the goal seemed to be extermination and it was completely reminiscent of the Nazi atrocities during WWII. When the war officially ended in November of 1995 there were over 200,000 casualties, of which over 120,000 were civilians. The number of wounded, displaced, and permanently impacted people is even more staggering.

From what we’ve seen, the siege of Sarajevo and the other attacks within Bosnia was not a war, although it might be called that. The history of this region is incredibly long and complicated, but what played out in Bosnia in the early 90s was genocide, and the Bosnian people felt completely abandoned by the international community. The UN came to be known as the “United Nothing”. Women in Sarajevo held a televised beauty pageant to try to get international attention and at one point stood behind a sign that read, “DON’T LET THEM KILL US”. It wasn’t until the Srebrenica massacre in July of 1995, where more than 8,000 civilians were killed in a matter of days, that the international outrage reached a high enough level start bringing an end to the slaughter. One of the most striking and poignant quotes we read was at the entrance of the Museum of Crimes Against Humanity and Genocide–“The genocide in Bosnia and Herzegovina was committed at the end of the twentieth century in the middle of Europe.” It’s too easy to look at the centuries of conflict within the Balkans and write off what happened in Bosnia in the 90s as just another internal spat among warring sibling-nations. But that’s not what this was, it was genocide committed at the end of the twentieth century in the middle of Europe, centered on a city that had hosted the Winter Olympics just a decade earlier in 1984.

It has been a new experience for us being in a place so recently stuck in the grips of war. There are plenty of signs around that the current political landscape here is not sustainable long-term:

- When we picked up our rental car in Belgrade, we had to name the countries we’d be driving to and then for good measure were told very clearly we could not drive to several countries (even though they weren’t on our list anyway), including Kosovo, Albania, and Bulgaria.

- One of the reasons we flew into Serbia to start our Balkans journey is that if you rent cars in certain other countries, you’re not allowed to drive into Serbia.

- Republica Srpska is still a functioning entity within Bosnian borders, despite the fact that it was created at the start of the Sarajevo Siege. It is primarily inhabited by Bosnian Serbs. According to our landlord, a lot of those individuals would still like that part of the country to join with Serbia. When driving in Bosnia across a Srpska line, it’s obvious where you are as there are large signs as well as Serbian flags marking the area.

- The presidency of Bosnia is made up of three individuals: a Bosniak, a Croat, and a Serb. The Bosniak and Croat are elected by citizens of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, while the Serb is elected solely by residents of Srpska. According to our landlord, these three leaders rarely all agree on something, halting forward progress and limiting investments in large future projects

What an incredible history learning experience for me just by reading your blog! Thank you so much, William, for sharing this part of the story, which I don’t really know a lot. I was shocked that the war lasted for so long but didn’t get recognized, nor did the United Nations intervene early enough. I wonder when you were there, what is your sense about whether the country or the people there are still impacted by such historical trauma? What do they want the tourists like you to learn about their history and country?

So fascinating!! Thank you for taking the time to write this all out. I am learning so much through your adventures. Keep sharing!

Thanks Renée, we’re really happy to have family and friends like you joining us through this blog!

Great questions! I think the country and people are still greatly impacted by the history, especially what happened in the 90s. Physical signs of the war are everywhere, and I’d imagine every citizen there who survived that time carries emotional scars around everyday. Our landlord very much wanted to get across to us that the Bosnian people are warm and welcoming and do not harbor ill will. He mentioned to this day his people are very much interested in unity with their neighboring countries, despite the history of violence, but that the interest is not reciprocated.

Hi Michael, my mistake of thinking this writing was done by William, but you are the one who wrote about this article…so much history unknown for many people! Your family is so brave and adventurous to go to Bosnia learning about one of the most recent history of genocide. Seeing that first hand must be one of the life changing experiences for you and your boys. I continue to pray for safety while you guys travel!

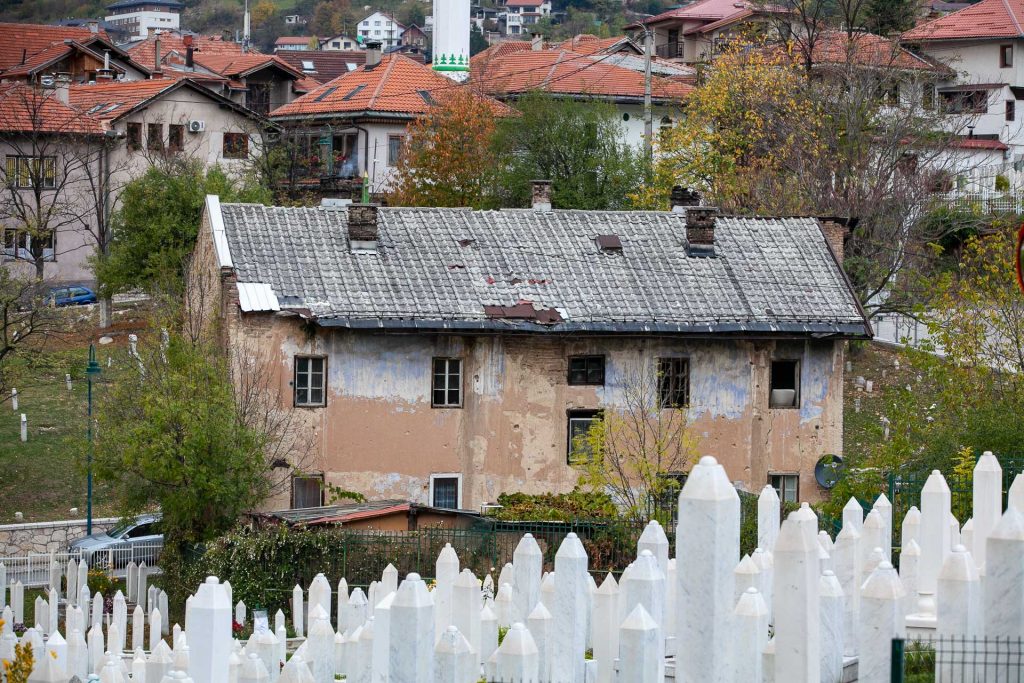

Thank you for sharing this perspective. The photo of the graveyard is especially moving and poignant.

Absolutely, those white gravestones were clustered all throughout the surrounding hills and really stood out, and still stand out in my mental images today.